Saskatchewan's First Successful Potash Mine Readying for its Final Chapter

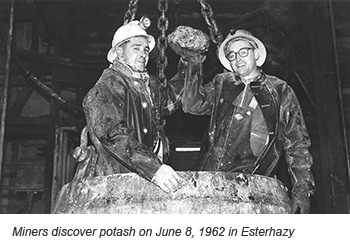

Fifty-eight years ago, after years of digging and toiling, miners reached potash in Esterhazy – unearthing Saskatchewan’s first potash mine.

Fifty-eight years ago, after years of digging and toiling, miners reached potash in Esterhazy – unearthing Saskatchewan’s first potash mine.

IMC Canada’s K1 mine – a predecessor company of Mosaic, was the first successful shaft-sinking project in Saskatchewan. Where other attempts failed, the project used an innovative ground-freezing technology that would allow safe construction through a high-pressure water layer occurring on the layered-journey through time to the valuable potash ore bed.

For over a half century, K1 has provided the world with around 285 million tonnes of potash – and locally, grown the economy and community.

Prior to the development of the K1 mine, Esterhazy was a town of about 500 people. As the mine turned up production, the area began to boom, with people and businesses flocking to the area, together establishing a community built on potash. Esterhazy soon became a thriving community of over 3,000.

Since then, the Esterhazy area has continued to prosper from its rich potash reserves.

“Thousands of men and women have put on their hard hats and coveralls to ride the ‘cage’ down to mine potash at K1,” says Esterhazy General Manager, Dustin Maksymchuk. “Starting in July, production will begin to wind-down underground at K1, and many will follow the well-worn route a kilometer below for the last time.”

An approaching farewell

An approaching farewell

Over the next three months, Mosaic will progressively ramp-down production underground at K1.

On September 20, 1962, K1 was officially declared ‘open’. It’s expected that primary mining at K1 will end close to the same time, 58 years later.

“Esterhazy is in an aggressive ‘transition’ phase, shifting its underground operations at K1 and later K2, to our state-of-the-art K3 potash mine,” says Senior Vice President, North America – Bruce Bodine.

The move to mine new K3 ore remedies several challenges that can come with mature mines.

“Between K1, and its sister-mine, K2 – the footprint of the underground roadways and mining areas span nearly the size of Winnipeg, meaning it takes a long time for our people to get to their work and back each shift,” he adds.

Next door, the K2 mine (developed in 1967) continues to fight an inflow of water that first entered the mine in 1985. With plans to mitigate the risk from the brine inflow and demonstrate a commitment to Mosaic’s potash future, a decisive decision was made to sink the province’s first new mine shaft in 50 years.

“In 2009, we announced plans to build the K3 mega-project adjacent to K1 and K2. In 2017, potash was struck. Much like on June 8, 1962, this milestone signified a new Esterhazy-era,” says Bodine.

K3 project on-track

K3 project on-track

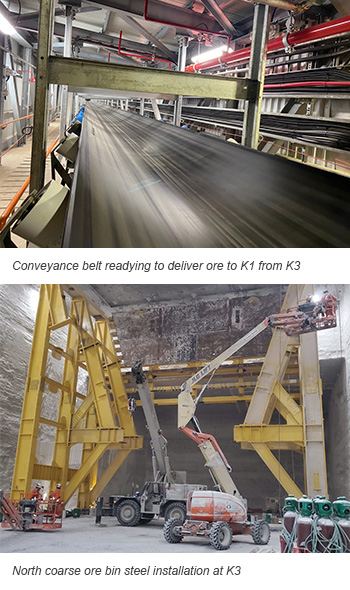

Today, on surface, work is underway to complete the south K3 headframe to match the impressive north headframe completed in 2012.

To end primary mining at K1, the overland conveyance system – an enclosed belt to move ore, will connect K3 to the K1 mill where the new ore will be processed. The conveyor is expected to start delivering potash this summer as the ramp down of K1 begins.

Upon completion of K3, Mosaic’s Esterhazy site is expected to be the largest, most competitive underground potash mine in the world. The full transition is targeted to be complete in mid-2022.

“Our transition is really a work-of-art,” says Maksymchuk. “Tightly coordinated milestones across three sites, all managed by teams of talented individuals who are building on the rich potash legacy for the area. Between managing our workforce, preparing operations, completing the project milestones, decommissioning planning and integrating new technology – there’s a great deal to synchronize.”

Shifting production from K1 to K3 signifies another major transition milestones and one more pivotal moment in Esterhazy’s storied potash past.

“We have a long and proud legacy here. For more than fifty years, we’ve managed to overcome great challenges and find success underground in Esterhazy. We’re ready for the next fifty and beyond,” adds Bodine.